Russian Tea: A Soulful Experience

Posted by Elena Yugai on Friday, March 22nd, 2013Tags for this Article: food culture, food history, Russian, tea

Russians love tea more than vodka. Even though it is vodka, bears and Siberia that became the ubiquitous symbols of Russian culture in North America, for Russians it is the tea drinking that stands at the very core of their identity and culture.

Tea became a country-wide tradition only around 1919-1920 as a result of the Red Army’s military successes during the Civil War. The Red Army won over large tea storage warehouses in Moscow, St. Petersburg and Odessa. Later, they also won control over several giant tea warehouses in the Urals region. This allowed Bolsheviks to supply their soldiers and industrial workers with free tea, which up until that point was considered an upper class product. During the Civil War, tea became a working class food staple and actually replaced vodka as a daily drink. The British Trade Union delegation that visited Russia in November – December 1924, especially those who remembered Tsarist Russia, were shocked at the near absence of drunkards in Soviet industrial cities.

Current Russian tea drinking habits are very different from tea ceremonies and traditions of other cultures. For example, the Japanese tea ceremony teaches calm appreciation of the small details surrounding the tea ceremony: the tea room, the tea set, the natural environment, be it a garden or the moon light. The main purpose of the Japanese tea ceremony is to appreciate the beauty of a tea drinker’s inner world. The Chinese tea ceremony, on the other hand, celebrates the tea itself, allowing the participants to discover the ever-changing nuances of tea flavour and aroma. And the English tea celebrates tradition, pride about preserving that tradition, and to some extent represents the British colonial legacy with its estate fine china, pastries and other tea-related accessories.

Russians, however, never had any strict ceremonies regulating their tea drinking. Every family, every social class in every region has its own drinking habits, though there are several general tenets:

1. Zavarka, a very strong tea concentrate is prepared in a separate tea pot. Boiled water is poured into a warm tea pot with several teaspoons of black tea, usually Indian or Sri Lankan. The pot is then covered with a clean kitchen towel for about 5 minutes.

In Central Asia it is customary to “marry the tea,” which means to pour out and pour back in an odd number of cups of zavarka. When it is ready, the host pours small amounts of tea concentrate into each guest’s cup and then dilutes it with hot water.

Zavarka has many advantages for Russian style drinking. It allows to adjust the tea strength according to individual preferences, but more importantly it allows the host to serve several rounds of tea to guests without having to constantly brew fresh tea. In the 1920s, when workers first acquired taste for tea, it was also considered a more economic way to make it last longer, though frugality is not a concern anymore.

2. The Fancy Guest china. Almost every family has a special tea set “for guests”. During the Soviet era, a beautiful china set was an important marker of the owner’s social status. The best ones were considered to be made abroad, and they were especially hard to find. My grandmother, for example, bought a Hungarian tea set in the early 1980s for my mother, and it still stands proudly in the china cabinet of my childhood home in North Caucasus waiting for a special occasion to be taken out.

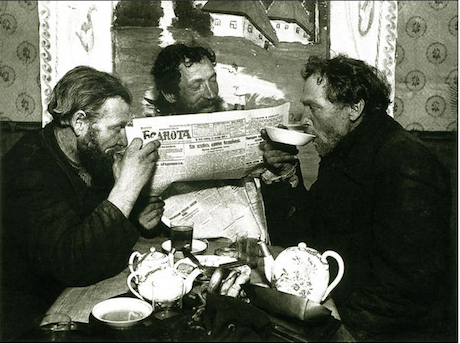

3. Tea cup, saucer and a tea spoon. Every tea cup must sit on a saucer and must have its own special tea spoon to mix in the sugar, honey, or jam. Some people like to pour the hot tea from their cups into the saucer to cool it faster and then drink their tea directly from it. It requires a certain balancing skill, and people are still debating whether it’s in bad taste to drink directly from a saucer or not.

4. Food. When you’re invited for tea in Russia, you can almost always expect to eat. Guests are offered several types of jam, honey, cakes, pies, chocolates and other sweets. Often you also get bologna or smoked kolbasa sandwiches, light salads, and fresh fruits and vegetables. Everything is served on ornate plates and dishes.

It is almost an insult not to offer tea to someone who came by your house, as it is an insult to refuse it when offered.

In some parts of the former Soviet Union, especially in the North Caucasus region and Central Asia, the amount and quality of the food spread when drinking tea indicates a level of respect that a host has for a guest, and it’s not uncommon for relationships to go sour just because only jam and sugar were served during tea.

But the most important part of the Russian tea drinking is the company and the appreciation of an honest, uncensored conversation, the soul spilling, the confessions, the tears, the laughter and the sacred camaraderie. In fact, it is the so-called “kitchen conversations” that gave an early platform for the development of radical intellectual and political ideas of the Soviet dissident movement in the 1950s and 60s, allowing the dissidents to freely share their ideas and visions for a better country within the safe confines of a private intimate tea drinking parties in the kitchen.

Tea is one of the most significant parts of Russian history and culture. It is a right of passage for children, who learn many of their values and beliefs by listening to long conversations that adults have during tea. It is a therapeutic space, where friends and family talk over their problems and find moral support. And it is even an important milieu for economic, political and cultural development of the entire country, as many business relationships, deals, and various collaborative projects are conceived, refined and agreed upon during tea. So, as far as cultural institutions go, it is tea, not vodka, that defines the Russian culture.

Posted on April 22nd, 2018

ayy says:

Never knew about that. nice info